It’s been about a year since I’ve had a period.

At first I was unfazed. I’d spent five years popping cute little pills of birth control and figured my menstrual cycle needed a minute to reach equilibrium. But then eight months went by, nine, and suddenly a year with no blood. The novelty of not having to buy tampons or deal with a week of bloating wore off.

I realized what had been true for months: I missed my period. I missed bleeding.

I got my hormone levels checked. My gynecologist read the diagnosis after a check-up as clammy as a preteen’s first hand-holding session.

“Your levels are all over the place,” he told me, a little too cavalier. “You’ve got PCOS. Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome.”

Ovaries? Cysts? A conversation with my mother years prior flooded back to me. She had cysts on her ovaries and one ruptured in her teens—the worst pain ever, she’d said. The doctors told her she’d be unable to conceive, but obviously they were misguided. My conception was a total surprise.

I’m 25 and not currently interested in bearing a child, but that’s beside the point. My diagnosis made me feel broken, like my female parts were in jeopardy. Like my womanhood was as precious as a flame and all the oxygen had left the room.

![]()

As a child, womanhood was a novelty: high heels, makeup, jobs that required power suits, cooking, New York penthouse apartments. I admired my Gammie when she was alive, the pearls she wore to church, the graceful way she guided us grandchildren by a gloved hand, her red satin bathrobe dangling amidst a mountain of makeup. My mother cooked dinner in a pair of heels. On Saturday afternoons, I watched her in the bathroom as she applied mascara and drank her coffee. She sat perched in on the counter, feet in the sink and freshly red lips painting the white porcelain of a coffee cup. I observed her seemingly effortless self-assurance. Womanhood was grace, power, and confidence.

Childhood went too quickly. My period came at 13 and I officially entered the coveted role of “teenager.” The excuse to ride a wave of mood swings, wander the mall without supervision, and earn an allowance came with an overwhelming discomfort to be in my body.

My sweaty armpits and mess of inconsolable curls did not match the controlled, cool composition of the teens I saw on television. I went on no dates and read obsessively, everything from Phyllis Reynolds Naylor to Stephen King to Teen Vogue. My best friend and I looked to Cosmopolitan and her older sister for information on what it it meant to be a woman. Blow jobs, boobs, tall, thin, white, smooth, career. Sex and shame dominated the glossy pages. Period stains were an OMG embarrassment. We drank in the stories from older girls on losing their virginities, mesmerized while we sucked the citric acid from a rare blue Sour Patch Kid, and wondered how something like that even begins to happen.

16, 17. I still I felt like an ungainly child playing pretend. My period and breasts were there, but where was the womanhood? I battled my curls, sandwiching them with four hundred degrees of heat until they were as flat as a strand of hay. I measured my waist and counted pieces of popcorn, calories beginning to rule my life like a clock. When my literary hero Hermione Granger was finally portrayed on film she was without the bramblebush of tangles that had haloed her in the books. Even she was now too cool for me to understand. Womanhood seemed so accessible for some, and yet for me, it was foreign.

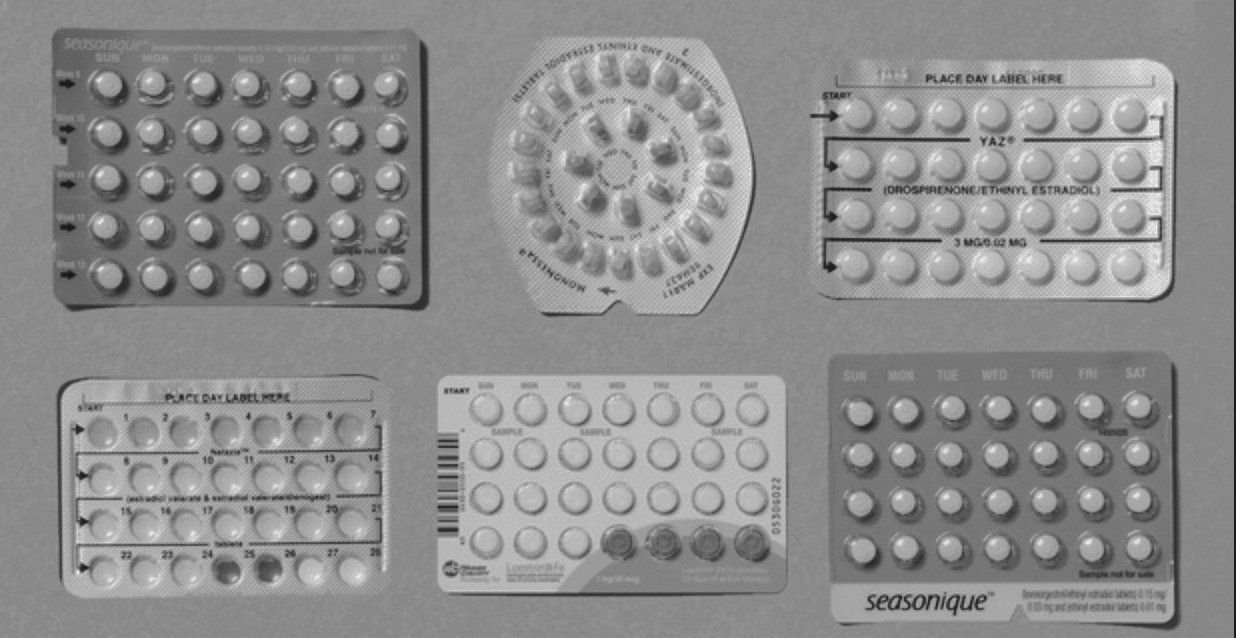

At 18 I went on birth control. The pill itself made me feel womanly (finally!)—a master of my menstrual cycle, my fertility, my sex. I carried the purple pouch around like a badge of honor, enjoying when the alarm on my cell phone bleated like a gentle reminder. Sometimes my friends and I would pop the pills at the same time and marvel in our adulthood. I relished this moment, an early sense of sisterhood blossoming the same way that it did when we simultaneously wailed about our broken hearts. To hate our lives was a form of camaraderie. Men suck, periods suck, being a woman sucks.

At 22 I was working as an actor in the Shakespeare company of a Renaissance Faire, living in the middle of the forest with no WiFi, and surrounded by historically-accurate representations of the 16th century. My roommate, Kate, had a copy of Clarissa Pinkola Estés’ Women Who Run With the Wolves and she read me excerpts before we went to bed.

The old one, the One Who Knows, is within us. She thrives in the deepest soul-psyche of women, the ancient and vital wild Self. her home is that place in time where the spirit of women and the spirit of wolf meet–the place where the mind and insticts mingle, where a woman’s deep life funds her mundane life. It is the point where the “I” and the “Thou” kiss, the place where, in all spirit, women run with the wolves.

Someone spoke to me. The One Who Knows? I felt something primitive rattle in my soul.

I left the forest and moved to Los Angeles, the capital of comparison. I lost a boyfriend, lost my period, lost the ambition for my career. Anxiety ate any chance for mindfulness. The calorie counting and multiple daily workouts came back. I didn’t know the woman in the mirror—the one who had spent so much of her life trying to figure out who she was becoming. A small part of me, the hungry part, remembered the words buried in that book.

I attempted to listen to the One Who Knows. I read, wrote plays, volunteered, and traveled. I meditated and practiced yoga, savoring the long stretches of my body, the soft part of my stomach when I lay in bed at the end of the day. I remembered that I was lucky to be doing this—that there were plenty of women who were not able to investigate their womanhood like I was. Ones who were forced to live under the thumb of a man, or have their gender nullified and their identity swept under the rug like a speck of lint. I promised myself to help other women find their voices and to spread word of our power. I wrote. A lot.

It was around this time that I was diagnosed with PCOS. After spending so much time trying to find my womanhood it was discouraging, a “Really? Still?” moment. After a lifetime of being uncomfortable and confused, I wanted so badly to be healthy. I wanted to respect my body as a woman, to work through health issues with self-love and attention. I saw multiple doctors with an innumerable realm of opinions. The affordable, easy options seemed thoughtless. The warm and holistic options were astronomically expensive. My Ayurvedic doctor told me, “It’s essential you come back to see me,” and then told me that my bill would be $180. Opinions swarmed like flies. Go back on birth control. See a naturopath—birth control causes infertility. Take vitamins. Get an IUD. Go to acupuncture. Eat more steamed kale. Don’t be stressed—stress will kill you. Plan your meals. Get enough sleep.

My womanhood is messy. It is curly hair and a belly and freckles. It is not always a period.

I did some of these things and I investigated support. One of the most beneficial things was to connect with other women with PCOS. There are so many; one in ten have the disorder and many find ways to thrive. (NOTE: This is not a PSA, but if you ever want to talk about PCOS, my door is always open. Sisterhood helps.) But the best thing I did was to listen to the wild woman, the One Who Knows, who told me to do the thing that felt entirely true to me: I packed up my car, moved out of Los Angeles, and spent a few weeks traveling the western United States, living out of a tent and sleeping in National Parks.

Alone on the road, the spark of my own wildness, my own womanhood, continued to grow. One morning, bathing in the canyon lake just at the border of Arizona and Utah, I realized something: Blood, height, hair—none of this mattered. The cool water against my skin. The sun drying my shoulder. My womanhood was a feeling. And it was entirely mine.

All of my life I felt like I was supposed to be something, and I never knew what the something was. But of course, The One Who Knows always does. She knows I am graceful, composed, and beautiful. And awkward and loud. My womanhood is messy. It is curly hair and a belly and freckles. It is not always a period. It is not associating with a specific sexuality; it is loving men and loving breasts. It is filled with loyalty and sisterhood and sleepovers where our feelings pour like tears. It is building a tent in the rain, high winds, and in blackness as thick as a sheet. It is carrying my boyfriend’s son through a grocery store and helping him select his snacks. It is loving the way my partner stares at my bare body and inhales all of my crevices. It is tasting and appreciating the earth through wine and plants. My womanhood is not limited to one definition—it is broad, sweeping, and ever-changing.

For those wondering, my period re-appeared. As is bound to happen with PCOS, the cycle is inconsistent and often painful. But I have sources now—women who understand that our womanhood is not defined by the shape of our body, or the texture of our hair, or the frequency at which blood falls from our legs.

Words cannot contain our wildness. Period.

LET'S TALK: