AND HOW YOU CAN HELP

There are those who are quarantined and those who are practicing social distancing—and then there are the essential workers, the folks who are showing up to work, emotionally drained, while holding space for the collective reality of COVID-19. Essential workers are grocery store employees, security guards, nurses, doctors, social workers, birth workers, law enforcement, and the list goes on.

Technically, I qualify as an essential worker as a social worker, however I say “technically” because I am able to do my work from home. I am based in Los Angeles, and provide trauma therapy to survivors of sexual assault and domestic violence. Interpersonal violence doesn’t stop when a pandemic hits the country. Rather, with no stretch of the imagination required, domestic violence often escalates when one is required to stay at home with an abusive partner.

Thus, my work has shifted over the past few weeks. Phone sessions and crisis calls fill the day from the comfort of the bedroom I share with my husband. As he works in the living room with music playing just loud enough to muffle any decipherable words from behind our closed bedroom door, I shift between video calls with my bosses to phone sessions with clients. As 5 p.m. hits, I close my laptop and turn off email notifications on my phone. I sage the bedroom. I crack the door and ask my husband if he’s ready to go walk. And then, we walk for a couple miles through the most secluded streets we know our neighborhood to have, working through this new normal.

There is immense privilege in being an essential worker who can work typical business hours from home. There is greater privilege being the one supporting others, creating a sense of safety even in the most unsafe environments, rather than being the one living in violence.

Julia-Elise Childs

There is immense privilege in being an essential worker who can work typical business hours from home. There is greater privilege being the one supporting others, creating a sense of safety even in the most unsafe environments, rather than being the one living in violence. As I comb through hot takes on how social distancing has been affecting others, I’ve been craving narratives from those providing essential services—those like me who are now separated from their clients but working together in a new way, or those on the frontlines protecting the health of the public.

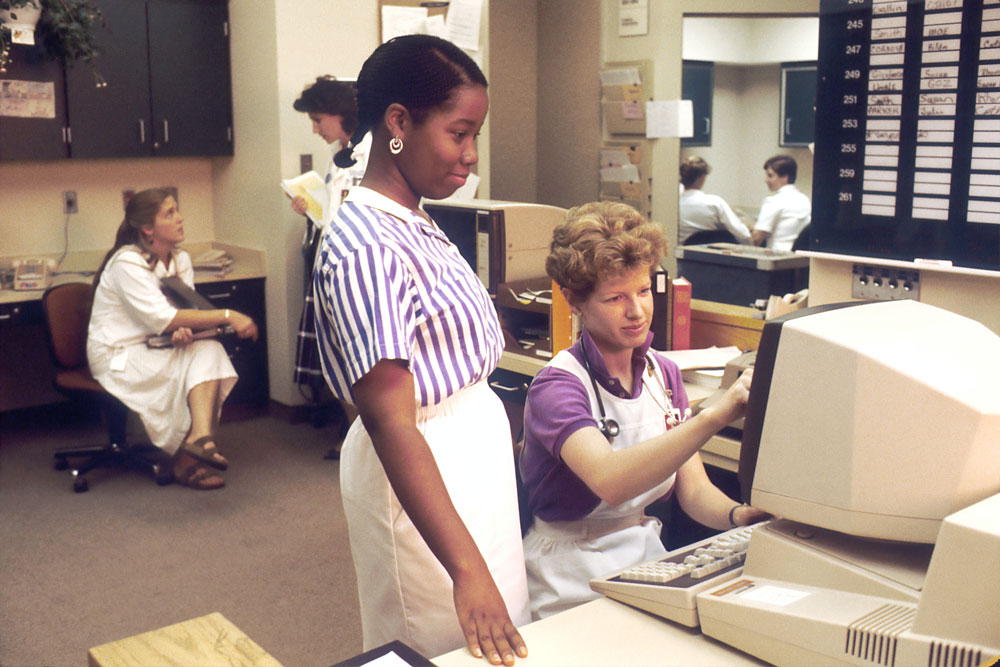

I turned to two dear friends of mine, Riley Mack, a doula in Long Beach, CA and Amira Jalaghi, a nurse in Phoenix, Arizona. I spoke to both of them about the essential services they are providing, how COVID-19 has affected the way they can show up for their clients, and what they wish the public knew about their work during this time. There’s an undertone of frustration when speaking to essential workers right now.

“Although I cannot be of much hands-on support at the moment, which is heartbreaking in so many ways, I have been working very hard to adapt to the needs of my first client/friend from afar,” shares Riley. The crisis of COVID-19 has devastating effects for birthing people in particular. The astronomical Black maternal mortality rate has Black-birthing people opting to call doulas and/or midwives into their birth plan. Yet, in response to COVID-19, some hospitals are not allowing doulas into the hospital as they are not considered “necessary” people. Racism kills and the layers of protection against COVID-19 attempted by the medical system has devastating effects for birthing people and those who support them. Despite this added distance for an essential need, doulas are innovative in their modes of servitude. “Some examples of how I have been showing up over the past few weeks include running short errands, making deliveries, conjuring custom herbal remedies, drafting birth plans—the list goes on.”

This sort of innovation has been a constant for many, not only during a pandemic. Riley puts it best, “I take great pride in our ability as Black and brown folks to get really creative in moments of chaos and disaster. The ability to tap into G.O.A.T mode comes out of trauma, for many of us, but I trust in our ability to alchemize.”

I take great pride in our ability as Black and brown folks to get really creative in moments of chaos and disaster. The ability to tap into G.O.A.T mode comes out of trauma, for many of us, but I trust in our ability to alchemize.

Riley Mack

Currently, Arizona is bracing for the COVID-19 crisis to flood their hospitals. Amira shares, “I definitely have anxiety before I go to work. Right now we are just preparing for it with an unknown question mark. Is COVID-19 going to hit Arizona hard? Do we have enough equipment? Are we going to be protected? Things are very ominous.” This sort of stress and strain on essential workers is both mental and physical. Nurses are equipped to encounter health risks while serving the public, something Amira makes very clear as she references an oath she took to serve the public as a nurse.

There is the question of who is checking in on the wellness of these workers. “The hospital I work at is screening anyone [from the general public] who comes in, but they’re not screening healthcare providers yet.” Yet. You read that correctly. I personally was in disbelief that those treating patients with COVID-19 were not being screened themselves. I ask Amira to elaborate. “Healthcare providers were just asked to not come in if they have symptoms and we were told we can go into 80 hours of paid time off if we get sick. But, all of this has been word of mouth. It is not being communicated effectively.”

Good vibes, prayers, and patience isn’t enough to support workers during a pandemic. We need to show up in other ways.

“Stop wearing [N95] masks unless you’re elderly or immunocompromised, and if you are, please stay home. Stop taking hospital equipment to treat your family or your community because then there won’t be any hospital providers—we will fall sick too.” Such a reality may sound harsh to those simply wanting to protect themselves as much as possible when grocery shopping—but those without must continue treating patients; preparing for the crisis to only get worse in their hospitals.

Our collective connectivity has never been more relevant. We cannot do a damn thing without one another.

Julia-Elise Childs

Donating to the creation of masks for medical workers is essential. Supporting legislation that protects the sanctity of birth workers, thus protecting the sanctity of birthing people is essential. I would like to encourage anyone who is at home with extra time on their hands to consider volunteering for a crisis hotline. Crisis Text Line offers remote training and all calls are answered remotely.

If you feel that emotional labor isn’t your currency, perhaps donating to organizations that serve survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault is a better option. Money is tight for many of us, maybe volunteering time to an organization working to get N95 masks to medical workers is something that sounds better. Or, maybe it is simply doing sanitized grocery runs for your elderly neighbor. Our collective connectivity has never been more relevant. We cannot do a damn thing without one another.

As we process our individual trauma, grief, and shock, we must remember those who are on the frontlines, fighting daily. Essential workers are also grocery store employees. Delivery drivers. Farmworkers. Janitors. Essential workers may not be documented. Essential workers may not be receiving livable wages. I hope we remember that these are the people who keep us comfortable, with food to eat and clean spaces to go. Remembering, we need to vote, act, and live accordingly.

I’m a nurse and I wish there were more conversations like this. How we support the medical community during these times etc. thank you for sharing <3

I’m a nurse and I live alone. It’s been awful coming home with no one to comfort me, no one to make me something to eat. Living alone has never bothered me until now.

I have been making large batches of food (ie- I made four meat loaves a few days ago) and delivering packages to my vulnerable neighbor and two older (senior) co-workers who are laid off. I used single-use aluminum pans so no one has to give them back. Next I’m making lasagnas.

I also made an appointment to donate blood for the first time and I’m going there first thing in the morning.

I love this conversation, we need to have more of them . So often as essential workers (I’m a child protection social worker ) we are caring and making sure everyone else is okay . We forget to take care of ourselves and others think of us as strong and don’t think we need to be checked on . We have to look out for each other and check in even when you think the person is the strong one .