Originally published October 30th, 2018

COMING TO TERMS WITH MY [RACIST] CHILDHOOD TRADITIONS

Last week, Megyn Kelly, a Today Show host previously at Fox news, had an all-white panel on to discuss what is appropriate and not appropriate to wear on Halloween. “The Halloween police is cracking down like never before,” she said, admitting this topic fires her up. While discussing cowboy and Native American costumes, Megyn brought up blackface, something she has trouble understanding the issue with, “Back when I was a kid that was okay, as long as you were dressing up as, like, a character.”

Social media responded, and the backlash led NBC to let her go from her own morning talk show. Since then, social media has continued to talk about blackface, and over the weekend several news outlets dedicated a short special on the topic.

Though I deeply understand the issue, watching the controversy and specials play, I was reminded of a time when I did not understand. Though it has a disturbing history, for me, blackface brings up many happy childhood memories.

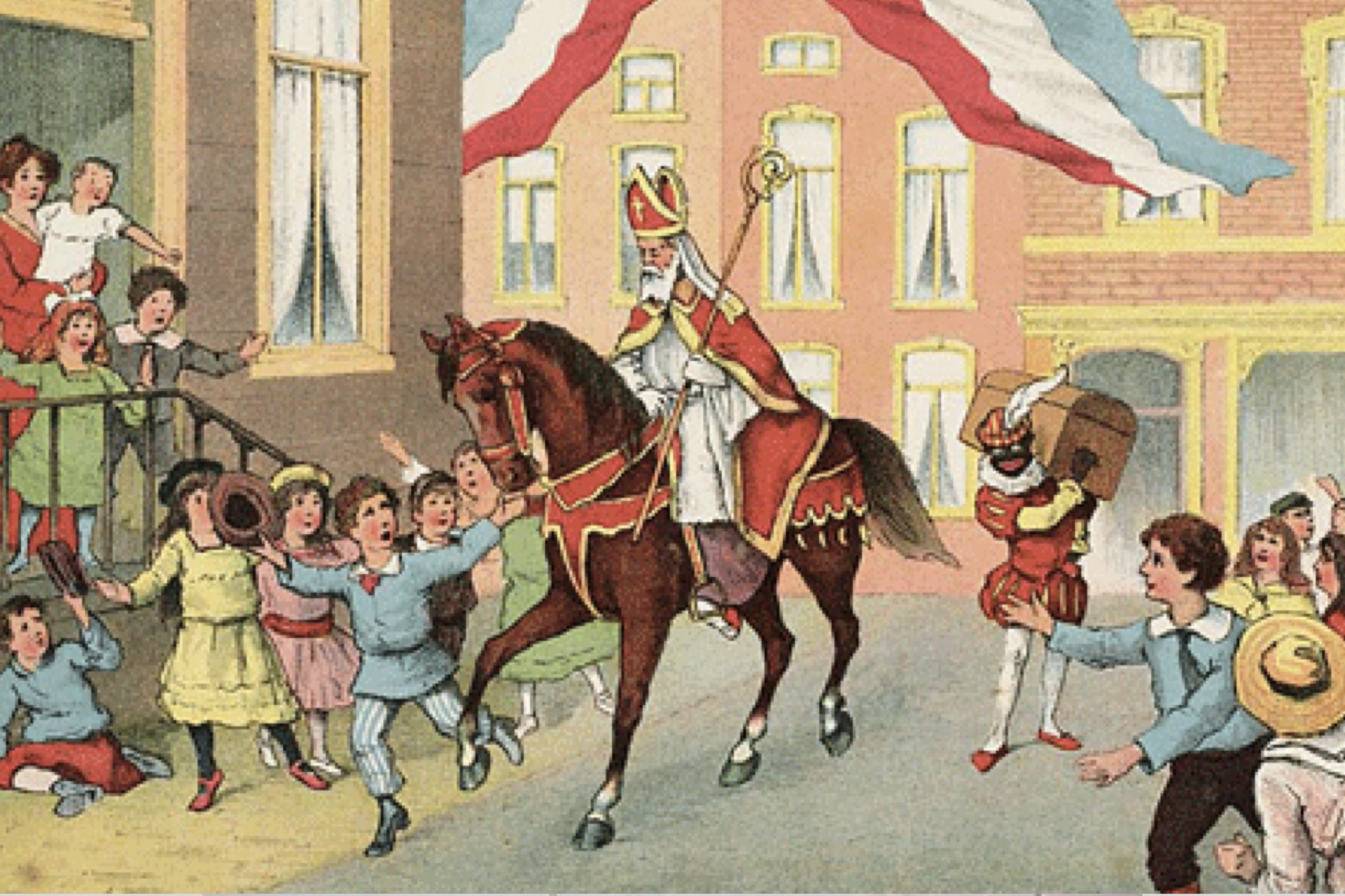

I grew up in Holland and Belgium, and on the eve of December 5th, Sinterklaas comes to town. He’s based on the historical figure Saint Nicolas, and you could call him our Santa Claus. Much like Santa, he’s an old white guy with a long white beard, dressed in all red, rewarding the well-behaved children with chocolates and gifts, and punishing the bad ones with no gifts at all. There are a few differences however. Instead of reindeer, Sinterklaas rides on a white horse. And instead of workshop helpers like elves, Sinterklaas has one guy named Zwarte Piet, which translates to Black Piet. He is viewed as Sinterklaas’ assistant, though in children’s books we learned about him as Sinterklaas’ servant. Black Piet helps wrap the gifts, carries Sinterklaas’ giant toy bag up to the roofs, and while Sinterklaas waits outside, Black Piet climbs down the chimney to deliver the gifts.

I showed him pictures of me dressed up as Black Piet. He couldn’t believe this was a tradition I participated in, let alone that thousands of people did the same, dressing in blackface at parades.

Alexandra D’amour

Growing up, no one dressed up as Sinterklaas to celebrate his arrival, but rather, all the kids and teachers dressed up as Black Piet. I have countless photos of my entire classroom dressed up in his 16th century noble attire, with lace collars and a feathered cap, and yes, everyone in blackface. If you type in “Sinterklaas parade” in Google, you will see thousands of people dressed up as Black Piet, blackface included.

I spent most of my childhood celebrating this tradition. I want to blame white people (my family included) for raising their children with these types of racists traditions, but my own brown mother, as well as countless families in my very diverse elementary school, participated in blackface. There was never mentions of it being racist. This tradition was considered festive, joyous, and more bizarrely, normal.

It wasn’t until in 2013 when Julianne Hough dressed up as ‘Crazy Eyes’ from Netflix’s “Orange Is The New Black” that I started to understand the problem. When I discussed the controversy with my husband, I then told him about Sinterklaas and Black Piet.

“You’re kidding, right?” he asked dumbfounded. “That is fully racist.”

I defensively responded by telling him that Black Piet was black because he was covered in soot from going down the chimney, which is what we were told as children.

I showed him pictures of me dressed up as Black Piet. He couldn’t believe this was a tradition I participated in, let alone that thousands of people did the same, dressing in blackface at parades. “This is one of the most absurd things I’ve ever seen,” he said, appallingly scrolling through the images.

It wasn’t until that year that I started to understand the problem by learning about the history of Black Piet. In 1850, Black Piet first appeared in print in a children’s book as the servant of Saint Nicholas. He would carry his heavy loads and wrap the children’s presents. The children’s book also instilled fear around his character. He would be the one to punish the naughty children by hitting them with a broom, or threatening them with kidnapping. The story gave you the sentiment that you shouldn’t feel safe around him.

When this book came out, slavery was still alive and well in the Dutch colonies. It would take another 13 years before slavery was abolished. Besides Black Piet, there were many other examples of blackface being used during this time. It was used to mock and dehumanize black people during the colonial period, a tool for oppression. Even beloved comic strips I grew up reading, like TinTin and Asterisk & Obelix, have versions of blackface throughout their series.

Learning about the history of Black Piet, as well as reading more about the protests that were happening in Holland that year against blackface, I first felt confused. This was not how I remembered Black Piet. He felt like a beloved nice guy, someone who would hand out candy and biscuits to children, someone that felt safe. But the longer I stayed in my memory bank, the more I recalled not-so positive memories. I distinctly remember black boys in my classroom being called Black Piet in a derogatory way. I recalled extended family members mocking Black Piet’s oversized drawn lips. “Black people have such big and ugly lips.”

While I now fully understand the issue with blackface, and am deeply embarrassed by the traditions I participated in, the protests against blackface in Holland and Belgium have been met with very strong resistance (and also within my family). A couple of years ago, my dad was yelling at the TV while watching the news, “Now they want to take away our traditions! What will we have left?!”

Anytime I’ve stated my opinions against Black Piet, specifically against blackface, to my extended family in Holland and Belgium, I’ve been met with lengthy conversations about memories, traditions, and the importance of carrying them from one generation to the next. People defend it because it was so important to their childhood, and it feels necessary to pass it onto their own children. What they were telling me was that the value of their memories, specifically ones that included these racist traditions, superseded the hurt they cause people of color. In other words, white joy takes precedence over black and brown pain.

What they were telling me was that the value of their memories, specifically ones that included these racist traditions, superseded the hurt they cause people of color. In other words, white joy takes precedence over black and brown pain.

Alexandra D’amour

I’ve noticed the same thing living in the U.S. when discussing Thanksgiving with Americans. Though most people associate Thanksgiving with turkey and football, this American holiday is filled with an oppressive history, one that is very often disregarded because of the importance of keeping traditions alive.

“This can’t be changed. It’s been around forever,” is a common sentiment I’ve heard when discussing both Black Piet and Thanksgiving.

While there is still a very strong resistance against the movement to get rid of blackface in Holland and Belgium, change is happening. After several years of protests, the Amsterdam city parade organizers decided to remove Black Piet’s racist and stereotypical characteristics by introducing Chimney Piet: an alternative character without the afro wig and exaggerated lips, and most importantly, without blackface.

History has molded traditions to fit a one-sided narrative, one that is white and oppressive.

Alexandra D’amour

Regardless if my childhood memories are sweet, the traditions I will pass down to my children will not be oppressive, or include damaging portrayals and stereotypes. I can’t believe I have to say this, but it feels necessary when speaking out against blackface: black people are more than characters, more than to be used for white entertainment. They are human beings. Period. And the traditions I pass down to my children will reflect that.

History has molded traditions to fit a one-sided narrative, one that is white and oppressive. My hope is that whether or not someone’s worn blackface, that we start taking a deeper look into our culture, specifically our traditions. Because often, we will find that traditions, even the ones that have brought us a lot of joy, are deeply rooted in a racist past, which is still very much present today.

While I’m happy that morning talk shows are dedicating part of their shows to discuss cultural appropriation regarding Halloween costumes, blackface should not be something that’s up for debate. My response to Megyn Kelly or anyone who disagrees with the idea that blackface is bad is very simple: childhood memories and traditions do not make something right, or less racist. Traditions are meant to be evaluated, especially if they are causing pain to anyone, but specifically to people of color. Your joyful memories are not more important than correcting a horrific past against black and brown bodies everywhere. Traditions shouldn’t be oppressive. Period.

It feels good to be around at age 70 and see this movement connected to Black Lives Matter, in the USA & in Europe, become stronger again!

Yes, I fully agree: ‘Traditions are meant to be evaluated, especially if they are causing pain to anyone, but specifically to people of color.’

As a Berlin woman with two black daughters – their father a former African-American GI – both born in the early 1980’s, my crusade has been intense. Three examples: *enter & protest bakery shops with the ‘Negerkuss’ label (“the negro’s kiss”, name of a German chocolate sweet), * argue with bookshop owners where the famous ‘Struwelpeter’ children’s book from the early 19th century was sold, in it the story of a disobedient boy who for punishment was transformed into a ‘black boy’ (by being put into an ink bottle) * write a letter in disgust to the curator of an exhibition on 19th century circus shows where you could see dehumanized ‘Mohren’ (name for Africans in colonial times) ‘imported’ from Africa, dressed up for entertainment of Europeans and displayed like animals in a zoo (without a BIG sign & a LARGE counter comment to all of that by the curator).

I would conclude, it’s the same as with the climate disaster we are in: For one thing, our political leaders have to publicly acknowledge that CRIMES ON HUMANITY have been committed (with the slavery of African-Americans, the shoah of Jewish people, the extinction of Native Americans, the destruction of Mother Earth … ) followed by deep mourning & immediate reparations. Second, to create that better, that humane world that is possible, our crusade needs to continue so that everyone can become aware & mindful and give up on their socially harmful habitual comforts. And obviously, the more privileged you are, the harder that will be … But the gain in individual & social self-respect is rewarding, I would like to add.

Greetings from Berlin,

Ute

real talk, idk my mansss, actually wait! in thanksgivinggggggggggg… like in elementary schhooool we had to like, dress up as the native americans, or the pilgrimss, and if you dressed up as a pilgrim you were allowed to like bring a toy nerf gun to school and stuff, and vice versa for the natives but like a toy bow instead

Who wants to be told they are oppressing another group of people? And even if we listened, would we care? Even within the Black community and Asian communities, men will deny the existence of colorism against women to maintain their own male privilege. Sometimes we act just like the gaslighting oppressors in our history. The truth is we as a society don’t care about others, just our own.