THE APPLE & THE TREE

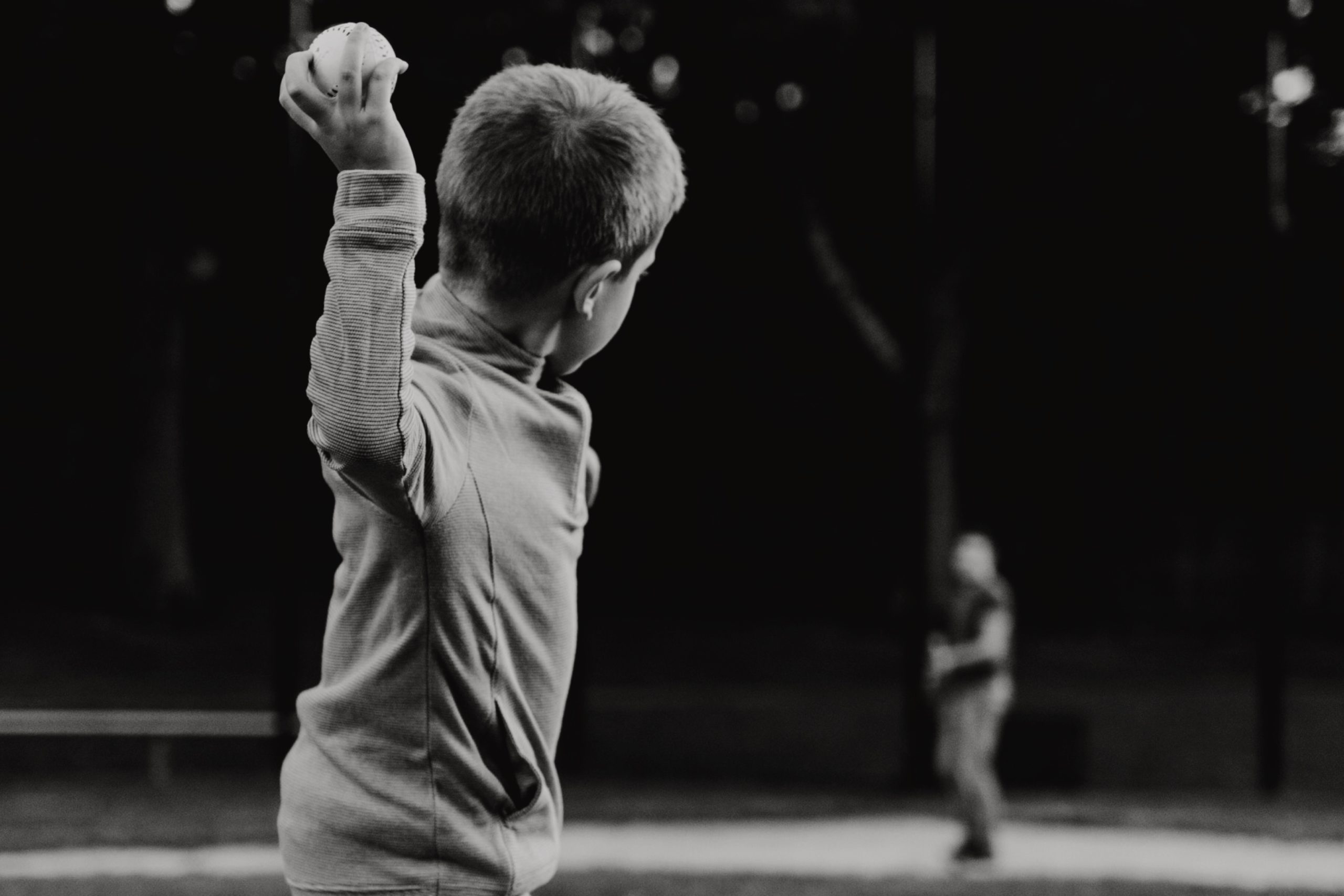

Like most kids growing up, I was mortified by my dad.

He loved literature, engineering, and geology, and he could drone on and on for hours about all three. He hated pop culture, and didn’t even pretend to care for sports or virtually anything else a pubescent boy would be interested in. He was painfully unhip. His uniform was an oversized undershirt tucked into elastic waist shorts, topped off with those geriatric, all-white ASICS and white socks pulled halfway up the calf. Diabolical, I know.

My dad was also kind of an asshole. He was a bit of a narcissist, with a hankering for one too many. He was moody, and prone to erupting when something bothered him. Never violent, physically—you were never actually struck by lightning—but the thunder clapped and the winds wailed. It was always best to hunker down and wait out the storm.

He was moody, and prone to erupting when something bothered him. Never violent, physically—you were never actually struck by lightning—but the thunder clapped and the winds wailed. It was always best to hunker down and wait out the storm.

Kevin Bones

Around the time I turned eighteen, we had a falling out. After years of pacifying his every fancy, I took a stand one night in a cheap motel in Solvang, California. If you’ve ever been to Solvang, you can understand how hilarious of a setting it is for a generational standoff. Dubbed “The Danish Village,” it’s a hokey tourist trap between L.A. and San Francisco, filled with pasty, sturdily built Nords riding tandem bikes and stuffing their faces with apple strudel.

Our showdown was about something inconsequential, and it really didn’t even create too many fireworks, but it sure as hell felt symbolic. On the precipice of manhood, I’d finally stamped my independence from his reign.

From that point forward, our relationship became more distant. He moved halfway around the world, so avoiding him became easier. He’d call occasionally and leave a message about “something I need your help with” or “some important news,” but I’d rarely call him back. Responding was the hook to be sucked back into the cycle—and I wasn’t falling for that, not anymore. For the first time in my life I felt light and unencumbered, liberated from the weight of the Death Star’s gravitational pull.

I’d succeeded in life, not because of any commonality we shared, but because I’d zigged everywhere he’d zagged.

Kevin Bones

As the years passed, my stance began to soften. We started talking on occasion, and I even visited him in Southeast Asia every few years. After I got married, I was surprised at how excited I was to introduce him to my wife. Together we visited him in Thailand, and a year later, he flew to Los Angeles and stayed with us for a few weeks. Spending time together wasn’t without its challenges, but it was generally pleasant and always made me feel a tinge of nostalgia for the more positive memories we shared.

My wife started drawing parallels between us after getting to know him. “Okay, Richard” she’d say as I was in the middle of commenting on “how fascinating the design of that bridge is” or embellishing my way through a story about some objectively mundane event. These comparisons would always catch me off guard, and I’d react defensively, dismissing any similarity in behavior. “Nice try, but this apple fell a country mile from the tree,” I’d chuckle, and then I’d change the subject.

He’d still robbed me of a normal childhood, and failed to protect me from the pitfalls of his own flawed relationship with his father.

Kevin Bones

Even though our relationship had normalized, I still regarded my dad the same deep down. He’d still robbed me of a normal childhood, and failed to protect me from the pitfalls of his own flawed relationship with his father. He was someone I’d survived—an obstacle overcome. I’d succeeded in life, not because of any commonality we shared, but because I’d zigged everywhere he’d zagged. He was the first stop in my decision-making matrix. “Would he do this?” I’d ask myself. If the answer was yes, Do Not Pass Go! Being nothing like my dad was core to my identity. It was how I’d been able to build such a secure, functional, and successful life for myself, or so I believed.

That is until recently.

I began to realize that very little about my life felt successful. Secure? Yes. Functional? Absolutely. But purposeful? In alignment? Far from it. Over the past few months I’ve come to realize that most of what I’ve found objectively distasteful about my life, are the very things my dad stands patently against: materialism and groupthink, banality and elitism. I’ve also come to realize that many of the things I’m discovering bring me happiness and passion in life, are things he unequivocally embodies: the importance and value of creative expression, a respect for and appreciation of culture, diversity, and history. They are the things I never would have been exposed to, interests and ideals never cultivated if it weren’t for his tutelage. Even the smallest of things, like the beauty in exploring places on foot or how to light up a room with a well-executed story (lightly sensationalized, for flavor).

I still have a lot to unpack between me and my old man, maybe more than we have time for to be honest. He’s eighty years old and lives halfway around the world, after all. But with the time we have left, I’d like to come to terms with the man that raised me. So I’m going to give him a ring today and get started.

I want him to know how badly he hurt me, a sentiment I’ve never directly communicated to him. I want him to know how grateful I am for all the unique life experiences and lessons he’s taught me. I want to thank him for instilling the importance of creative expression and forging your own path, both of which are such critical elements to the new chapter I’m embarking on now.

Most importantly, I want to tell him I love him. Because with sharing and love, comes healing. And even at thirty-two and eighty years of age respectively, it’s never too late.

LET'S TALK: