I call my mom often from college to give her updates on my curls. She doesn’t care. She tunes out every time I bring up my natural hair journey. She doesn’t realize what it means to me. The vital role it played in discovering my black identity. The lessons it taught me about the intersection between blackness and womanhood.

It’s not the first time my mom’s rejected thinking about blackness. Recently I helped her create a Bitmoji (she’s catching up to the times, y’all), and when I finalized her character I watched her eyes widen and then narrow as she looked at it. Considering that Bitmoji was some of my best design work yet, the crease of her brows confused me. She shook her head.

“It’s too dark. I don’t like it.”

“But mom, this is your skin color. If I change it, it won’t look like you anymore.”

She pressed her lips together and let out an exasperated sigh. It became clear to me that this Bitmoji was not just about shits and giggles for her. It was about representation. And she was not willing to let dark skin represent her.

I was raised not to think about my blackness because my mother was raised not to think about hers. When it came time for her to have a child, she was artificially inseminated with some white guy’s sperm to make me: a caramel-hued woman with fine, 3b curls and a big butt.

When I was a baby people didn’t believe my mom and I were related because my skin was so fair compared to hers. On standardized tests I used to scan right past the “Black or African American” box and check “Two or More Races.” Because technically that’s what I was, right? I mean, I didn’t know anything about the white side of me, but I supposed it was there.

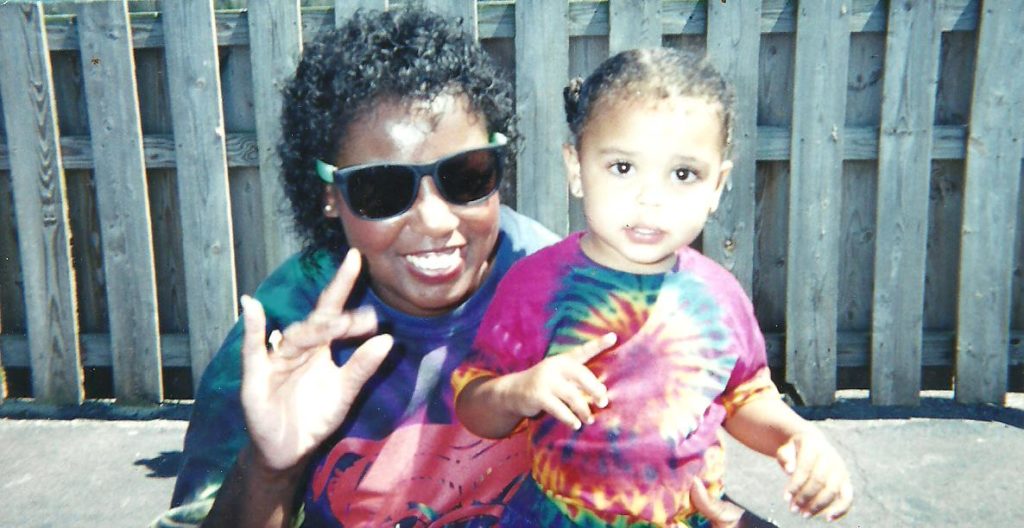

The author and her mother

I was raised with white dolls. I remember playing make-believe with them in my basement. I was their blond-haired, blue-eyed mother, happily married to my successful husband (also white, also blond). The few black dolls I did have were my adopted children; I was their rich white mother—a celebrity and savior. I blame Hollywood for that one.

I was raised with white people. We were the only black family at my church and in my neighborhood. My friends were white. My teachers were white. The girls in the movies I loved were white. The boys I crushed on were white. On paper even my name was white. There was nothing that had me clinging to a black identity.

I was raised to fit in with the white kids. I did well in school, played classical piano, took ballet, tap and jazz, joined Academic Challenge, attended youth group on Sundays, and a writing club on Tuesdays. And after all that was said and done, my self-care routine consisted of frying my ends with a flat iron until the entire upstairs reeked of smoke. Whether it was my music, my hobbies, my clothes, or my voice, kids at school always found a reason to call me an Oreo—black on the outside, white on the inside.

I was so far removed from blackness that I couldn’t recognize it on myself and when I saw it on others, I really didn’t know what to make of it. My peers told me I wasn’t really black; I “didn’t count.” And the more they told me I didn’t “count” as black, the more I began to believe them.

I went to my first black party. Is there a word for experiencing culture shock in what is supposed to be your own culture?

Sometimes it was meant as a compliment. Like I had somehow been blessed, or accomplished some sort of superior status. I’d usually shrug it off. Occasionally I’d call them out on their racist BS, but part of me wondered if accepting it as a compliment meant rejecting who I was. Is being black who I am?

Besides little reminders of blackness—sitting at the stove by the hot comb, smelling the greens heat up in the pot while the cornbread baked in the oven, or my uncle popping in yet another Madeamovie (I mean, really, how many can there be?) on Thanksgiving—the thought of being a black woman never crossed my mind.

It should come as no surprise, then, that I went to a predominantly white institution—a PWI—for college. It was the kind of campus where you could walk from one end to the other without passing a person of color.

I’d received an academic scholarship that was granted to minority students. Because of this, I arrived a few days early for the orientation program where we were all connected with mentors and small peer groups to lean on throughout the year. For once, I wasn’t one of the only black girls in the room. I made my first college best friends. My first black best friends.

A few weeks later I attended a Black Student Union meeting. I was in a room full of black people. There were probably forty of us, which might not sound like a big deal—it was a BSU meeting, after all—but I couldn’t think of a time in my life where I’d been around so many black people at once. It was casual and informal. We hadn’t been singled out. There were no white faculty members reminding us of their departmental commitment to diversity. I realized that BSU was kind of like a safe haven; somewhere to escape to when you needed a release. Many of these students came from cities and schools and churches where black is their norm. For them, BSU was like a piece of home.

For me, this was nothing like my norm.

I went to my first black party. Is there a word for experiencing culture shock in what is supposed to be your own culture? Forty black people in a room was nothing. This place was claustrophobic. Honestly, I was not comfortable. I didn’t know the songs. I didn’t know how to twerk. My clothes were not on point and my makeup was not on fleek. I was still acquiring my taste for “jungle juice” and trying to navigate looking “cool” while sipping it. I stood apart from the very people who looked like me. And not just in the typical “freshman” way. It felt like since I got to college, blackness was being thrown at me every which way, from new hairstyles to African American studies courses, to politically charged messages on the school’s graffiti wall, to the word “diversity” fed to us with every bite. Colleges really love that word.

They had to find people to support them, believe them, believe in them, push them, laugh with them, grow with them, and see another day with them. Because joy can be snatched from you just as easily as it can be handed to you when you’re black.

It was becoming information overload and I just wanted to ease into it, to process it.

But there was no way for me to ease into it. It was 2014, and that November word went around that students were meeting up on College Green to listen to the grand jury decision on Officer Darren Wilson, the police officer who shot Michael Brown.

I went with my best friend. Someone held up a radio while others checked updates on their phones. It was nighttime and chilly; students clung to one another partly for warmth, partly for the shoulder they might soon need to cry on. The official announcement came through: No charges would be filed. I felt a collective river form with tears of an indescribable weight. Our hearts were made of eggshells. One more injustice and they’d shatter for good.

We marched in a line toward the student center chanting:

“Which side are you on friends? Which side are you on? Justice for Mike Brown is justice for us all.”

We formed a hollow circle of solidarity on the top floor of the student center, holding hands and crying. More people arrived and the circle grew bigger.

It was in that circle that I knew, truly knew, that I was black. I looked around and saw people whose skin reflected my skin—black in all hues and shades. Our hearts beat and stung the same. I watched as people who looked like me chanted Black lives matter!—a movement that was just beginning. I saw the photos of Mike Brown. I saw the tears of my peers. I heard their voices shake. I knew that I was a part of this. This too, was my reality. These too, were my people. This was my pain. And this is was what happens to people like me.

I wore this black skin all my life but I never noticed it until now.

I understood why we needed a BSU. I understood why we needed black Greek life and black parties and black organizations. I understood why most of the black kids at school all knew each other. They had to survive. They had to find people to support them, believe them, believe in them, push them, laugh with them, grow with them, and see another day with them. Because joy can be snatched from you just as easily as it can be handed to you when you’re black. They had to be freely themselves. They were not invisible or replaceable or disposable. They were black and proud of it.

We have to give black girls extra love by making an extra effort. They deserve to know what it means to be black. They deserve to know it can mean anything they want.

When I came to college, I saw black girls with natural hair, box braids, scarves, and locs. I saw black men with dreads and cornrows. I saw black people who aspired to be surgeons and lawyers and engineers and journalists and activists. I saw black people who could dance and sing and create music. I saw black people who won scholarships and awards and studied abroad. I saw black people of all different styles, all different interests, different tastes, different looks, different backgrounds, different lives. I finally saw me. I finally knew which box to check.

I wish I had been taught that black comes in all sorts of tones and shades. I wish I had been taught how to do my natural hair. I wish someone had taught our history—about black girls who flew planes and played instruments and led movements and wrote books and improved science. About black girls who loved and were loved right back.

We have to give black girls extra love by making an extra effort. They deserve to know what it means to be black. They deserve to know it can mean anything they want.

Young black girls need dolls with hair and skin like theirs. Black girls need to know how lucky they are to be black; to have skin that was kissed extra by the sun and looks fabulous in yellow—in every color, if I’m being honest. I wish I had seen movies with two black lovers, with black heroes and protagonists. I wish I had been told that black lives mattered. I wish someone would have told my mom that, too.

My mom chose to give me white features so that I could be more beautiful and have a better life. But when I detangle my hair and lotion my skin, I’m beyond happy I got her black features, too. Because this black skin is a piece of her I get to carry with me and honor. It’s a piece of where she came from and the mothers before her. It’s my ancestral connection. My roots. My rhythm. It’s a collective story. It’s black girl magic.

And I’ll be damned if anyone calls me Oreo.

Amazing writing Abigail! You have expressed your journey so eloquently and I so admire your honesty! I look forward to reading much more from you in the future!

Thanks Abigail for sharing your truth! I am inspired by your story and intend to share it with my students. I hope your story can bless them now in some way.

“My Mom chose to give me white features so that I could be more beautiful…” I really want to believe this means something else, but it’s up to the writer to carefully and thoughtfully articulate such ideas. This statement translates as “white” features are in fact more beautiful after all. Yikes.

My mom grew up suppressing her black identity and struggling in her own skin. She did not feel beautiful, so when the opportunity came for her to have a child through artificial insemination she chose features for me that she wished she’d had. Features that, at the time, she believed would give me opportunities that would help me get ahead in life. It makes me sad to know that my mom didn’t see her dark skin as beautiful; I think her skin and black features are the most beautiful things on earth. I was writing through the lens of how my mother felt. But I understand how you felt this way. I appreciate you for reacting and speaking up, truly.