I NEVER LOST MY BODY. I ALWAYS HAD IT.

People have been telling me about my body for most of my life. Family members, friends, and strangers have lent their personal opinions at some point. My body has been called thick, fit, and average. Someone told me I “lost it” when I became vegetarian and lost weight. And when I “got it back,” another person called my body inappropriate.

As a Black woman, these comments are also coupled with the refrain “Black don’t crack!”, a long-standing expression in the Black community used to laud people who look years younger than their actual age. I’ve had people tell me I look a few years younger or—mercifully—my exact age.

These commentaries created the standards that I held myself up to for comparison. When examining my body in the mirror, I smoothed my face and wondered how I could look forever young like Bianca Lawson. I flexed my arms, and imagined how many squats and pushups I’d have to perform to get close to Angela Bassett’s physique. I constantly wondered where my body fell on the attractiveness spectrum.

These obsessions clouded my mind with greater fervor when I first glimpsed my body after my first pregnancy. Like many mothers, I was warned that my body would not return to its pre-pregnancy size and weight once I gave birth. But the reality of it was disorienting. I stared at my daughter, swaddled in her crib, and then at my belly. I experienced an emotionally flattening moment of cognitive dissonance. My daughter was out of my womb, so why did I still look pregnant?

I was uncomfortable with the way that I looked—like myself but a bit distorted. My shoulders and hips had widened. My feet lengthened from a size 11 to a not-quite-size 12. Everything else became plumper and fuller. This discomfort was amplified by the fact that most of my clothes didn’t fit. My pre-pregnancy clothing was too small and, while ill-fitting, my maternity clothing was all that I had available. The buzzy patterns and ruched sides only made my body look more unflattering.

I constantly wondered where my body fell on the attractiveness spectrum.

I tried to find solace on Instagram, which in retrospect was not a wise idea. The media platform was an unhealthy source that fed my self-rejection. I snooped on other women who had also just recently had children to see how they were coping with their postpartum bodies. They looked as if they had never even had a baby. Their followers praised them—with some using them as a standard to criticize other mothers who hadn’t regained their pre-pregnancy bodies.

Thanks to hashtags and algorithms, I also saw more posts related to postpartum fitness than I cared for. Everyone from models and celebrities, to friends of friends, were humble-bragging about their postpartum snapbacks. I compared myself to them and determined that I was not doing enough to make my body change back to its normal self.

Self-consciousness quickly took over, and I felt the need to explain myself to everyone. I wanted to tell them that the reason I looked bigger was the fault of my pregnancy. Most importantly, I wanted to scream out that I didn’t normally look like this. So often when someone looked at me I would defensively cross my arms over my belly and resist the urge to say, “It’s because I just had a baby.”

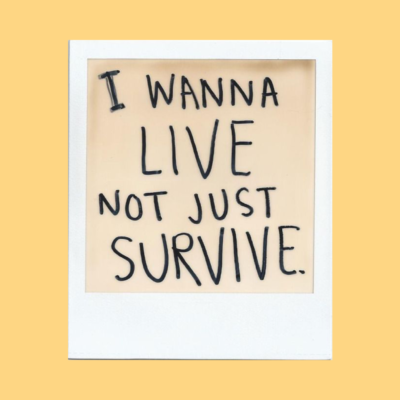

It became so difficult to accept myself that it began to wear on my mental health. I was dipping in and out of depression, and my attitude sucked. I was sick of hearing myself complain, and I was tired of never looking in the mirror because I was ashamed of what I saw.

At some point in that first postpartum year, my mindset changed. I’d like to say that I turned to body positivity for my daughter, or that I learned to love myself so that I could teach her to accept her own body. But in truth, I just desperately wanted to feel like my normal self.

One day as I got ready for a shower, I stripped off my clothes and stared at myself in the mirror. I caressed my fleshy stomach and my thighs. I hugged my body and stared into my eyes, telling myself that I was beautiful, and I loved every part of me.

Every flattering compliment about my body informed how I saw myself. I based my self-worth on other people’s compliments and when I didn’t receive their praise, it was damning. Consequently, I never loved what I looked like to myself. I loved what I looked like to other people.

In the weeks that followed, I often examined my changed body. After regularly staring at myself in the mirror, I realized that most of my shame was rooted in fear. I hadn’t allowed room for my body to change. I was stuck on this idea that it was immutable. I had been fighting who I was becoming and now it was time to just let myself be.

Now, I meditated on the natural, physical changes that came with creating and birthing new life. I acknowledged my new normal.

The healing process was not sudden. It was long and arduous. I began dismantling my idealized self that was born out of other people’s opinions of me. I discovered that I was framing my body around comments I had internalized since adolescence. Every flattering compliment about my body informed how I saw myself. I based my self-worth on other people’s compliments and when I didn’t receive their praise, it was damning. Consequently, I never loved what I looked like to myself. I loved what I looked like to other people.

I started complimenting myself daily. I stared at my reflection and said I looked great, pointing at specific parts of my body, and said what it was that I loved about them. I wasn’t trying to convince myself. I was opening my own eyes to who I was. I was changed, but still there.

I never lost my body, and it never needed to be found. It was simply waiting for me to embrace it.

photography by Anita Cheung

Hi