Growing up, I learned two different vocabularies around food. These vocabularies were similar in intensity, but opposite in every other way.

The more positive vocabulary was developed primarily at home, among family and friends. In this world, happy occasions were celebrated with cake and cookies, vacations were peppered with delicious treats, and any time I came home with a good report card it was up to me to choose the dinner menu. My mom, a naturally petite woman who by her own admission “doesn’t think about food,” was careful to keep scales out of the house and to keep the conversation around eating and weight largely positive.

I learned my other food vocabulary in health class at school. There, I became familiar with words like “anorexia” and “bulimia.” I learned to look for signs that people around me might be suffering. I knew from the way my teachers’ voices dropped when they spoke about these subjects, that these big words — eating disorders — were not to be taken lightly. As a child of the nineties, I grew up an unwitting consumer of less intense but equally problematic messaging about body image and food consumption. It was the age of SlimFast commercials and exercise equipment infomercials after all, which meant there were a lot of wild before and after photos flashing across my TV screen.

For years, I operated under the mistaken impression that disordered eating could be approached and discussed only in two extremes. You could be “good” at eating, by using foods to celebrate big moments and not stressing about it otherwise — magically maintaining your weight all the while. Or on the other hand, you could eat and get fat, or not eat and be placed in an even scarier category as “sick.” I had no idea there was a spectrum in between.

I was just a little weird, a little extra careful about what I put in my body, a little more sensitive to stress and anxiety than others, or at least that’s what I told myself.

Alli Hoff Kosik

Because of my lack of understanding about this gray area, it wasn’t until I was in my early to mid-twenties that I could more clearly see that so many of my own behaviors around food were verging on the unhealthy and leaning toward disordered. When my nearest and dearest began to comment about my obvious weight loss during stressful periods, and when a therapist I was seeing for unrelated issues pointed out that my daily routines with food and exercise were potentially obsessive, I had to reflect on my behavior.

I had to think about the many days of my teen and college years when I’d secretly challenged myself to go as many hours as possible without eating.

I had to recall all of the times that I’d immediately jumped on the treadmill after eating a big meal.

I had to remember the random fasts and cleanses I’d tried, for no real reason.

I had to confront the more difficult memories associated with infrequent, yet habitual episodes of buying laxatives, of binging and purging. I had to admit to myself that my habit of running to the corner store to buy — and then quickly eat in secret — a bag of chocolate-covered pretzels on a bad day at work was more than just a quirky coping mechanism. It was an unhealthy, disordered behavior.

My problematic habits might not have required medical attention, but they were problematic nonetheless.

Alli Hoff Kosik

Having (rightfully) learned from a young age that an eating disorder like anorexia or bulimia was so serious, I couldn’t see the truth about my own unhealthy habits. After all, I was still going about my business as usual! I had plenty of energy to exercise, and I went grocery shopping like everyone else. My body didn’t look like the photos I’d seen in health class of people struggling with eating disorders. I was just a little weird, a little extra careful about what I put in my body, a little more sensitive to stress and anxiety than others, or at least that’s what I told myself.

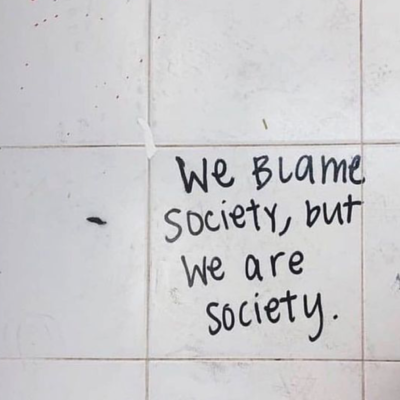

And I know I’m not the only one caught in a gray area of disordered eating. Crash dieting, exercise bulimia, and occasional moments of restriction, binging, and purging seem like normal, everyday responses to the societal pressures we feel to look good and be thin.

The complexities and widespread nature of eating disorders and disordered eating affect at least 30 million Americans of all ages, according to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders. This equates to approximately one percent of the population. Per the same organization, 13 percent of women over the age of 50 engage in disordered eating behaviors. According to Healthline, eating disorder treatment centers have seen a 42 percent increase in women over the age of 35 seeking help in recent years. Per the same article, disorders are often triggered by transitions that occur later in life — the death of a loved one, divorce, illness, or becoming an empty nester. Many women may not have been ready to seek treatment when they were in their teens or twenties, and decide to get help when they relapse later in life.

Given my own struggle for so many years, that doesn’t surprise me.

My inability to see the problems with my relationship with food was rooted largely in the fact that I’d never even heard the phrase “disordered eating” until I was in my mid-twenties. Conveniently, my understanding of it came around the same time that I was reckoning with my own disordered patterns. Suddenly, it all came together. While in the thick of a big, scary professional transition, I started getting real about all of the bad habits I’d failed to recognize. If I’m about to uproot my work life, I might as well deal with some of my other skeletons, too, I thought.

My inability to see the problems with my relationship with food was rooted largely in the fact that I’d never even heard the phrase “disordered eating” until I was in my mid-twenties.

Alli Hoff Kosik

For the first time, I told my husband the truth about all of it. Throughout our relationship, he’d known that I could be obsessive about food and exercise, but it was time for him to know about my inconsistent eating in college, about the laxatives, and about my snack binges. I sat across from him on the deep-discount couch in our first apartment, and put words to my behavior for the first time. We worked out a plan. If I felt myself approaching a disordered behavior, I would tell him about it. It was simple, but powerful. I was finally giving myself permission to call it a problem; a problem that needed to be looked after.

Armed with a better understanding of what I was doing, I doubled down on establishing more reasonable, actually healthy habits. My husband and I started to cook together more and bought a few new cookbooks. I committed to giving my workouts a better, more relaxed structure, and tried to think of my runs as an appreciation of what my body can do, rather than thinking about how it looks.

These days, while I still live somewhere between those two food vocabularies, I’ve also learned to respect my body too much to embark on the downward spiral of my old ways. I know there will be days when I wake up on the wrong side of the body-image-bed, and remind myself to be patient and seek accountability with the people I love. I drink a healthy smoothie every morning, and rarely feel the temptation to restrict myself at dinnertime, and while the gym is still one of my favorite places, I now work out because I love my body, not because I hate it.

I still have a hard time talking about my experience with disordered eating, and I can only imagine that it would have been easier for me to do so if I’d understood it earlier. I could have gotten real about my own unhealthy patterns, shared them even earlier with people I trust. My problematic habits might not have required medical attention, but they were problematic nonetheless. I wish I’d known earlier I could not only find support, but also feel better.

LET'S TALK: do you have a "grey area" eating disorder or disordered eating habits?

1 Comment

WHAT READERS ARE SAYING ABOUT THIS ARTICLE